Author: Olga Goralewicz, ACT Specialist

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (pronounced as the word “ACT”) focuses on developing psychological flexibility and mindfulness for a better quality of life. It is a form of psychotherapy that teaches patients to:

- let unpleasant thoughts and feelings that are out of your control come and go, and

- take action towards living a life you want to live.

Can Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) help me?

Research shows that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is effective against:

- anxiety disorders,

- depression,

- obsessive-compulsive disorder,

- borderline personality disorder,

- stress,

- post-traumatic stress disorder,

- substance abuse,

- schizophrenia,

- burnout,

- chronic pain,

- and more.

If you suffer from any of these psychological issues, you may want to reach out to an ACT therapist. Nonetheless, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy can be administered as self-help.

This psychotherapy is very flexible. It can be customized to individual, couple, and group therapy and conducted both short- and long-term. The form allows therapists to tweak and even co-create the techniques and strategies with patients.

How does ACT therapy work?

In ACT, the goal isn’t to “cure” any symptoms, but to learn not to struggle with them. Symptom reduction is a desired side-effect.

Acceptance and Commitment therapy trains psychological flexibility. After learning key strategies, you can distance yourself from so-called private experiences, which may include your thoughts and feelings, but also sensations, urges, and memories. Patients are encouraged to accept that not all are pleasant.

What follows is that ACT does not aim to reduce negative private experiences. In Western psychology, those are often labeled as “symptoms” of a mental disorder. In the spirit of ACT, trying to fight, change, or alter painful thoughts, feelings, and sensations is what leads to struggle in the first place.

In the understanding of ACT, patients approach struggling in two different ways. One way is referred to as dirty discomfort, while the other, fittingly, clean discomfort.

Fighting or struggling with a feeling is what leads to dirty discomfort. When your struggle switch is on, you end up in a vicious cycle. For example, if you are experiencing anxiety, trying to get rid of it by forcing yourself to calm down can make you more anxious. Angry, even. “Why is this happening to me?”

Clean discomfort is when you accept that you are feeling anxiety without fighting it.

Russ Harris compares this struggle to sinking in quicksand. Instead of fidgeting and trying to escape, which increases suffering, you should become immobile. When undergoing an unpleasant private experience, such as anxiety, a healthy relationship with the feeling will help you live through it and it for what it is. Without any unnecessary emotional baggage.

What’s more, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy rejects the Western psychological notion of a “healthy normality”. This premise assumes that when given a healthy environment and social context, humans are always happy and content. In this understanding, anyone who suffers from mental issues is a product of their environment.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy proposes instead that cognitive processes are often destructive, no matter what the situational context is. The root problem of mental issues such as anxiety is a strong focus on trying to avoid associated thoughts, feelings, and sensations.

Relational Frame Theory and ACT

ACT is based on Relational Frame Theory (RFT), which explores language as communication not only with other people but also with the environment and our own minds. According to RFT, the mind is no more than a system of thoughts and cognitions, so it can be understood as simply “language” as well.

In the context of this theory, “rational thinking” and “problem-solving” are our most basic patterns. When we encounter something we don’t like, a problem, our immediate reaction is to try to come up with a solution.

While this is great for some situations (eg. It is raining, I don’t want to get wet, I will take an umbrella) it may be completely destructive in others (eg. I experienced a minor setback at work, therefore I am worthless, I should quit). The latter is an example of behavior that is referred to as experiential avoidance.

Many studies show that experiential avoidance does not work to solve mental issues. The end result is shutting yourself off from situations that may actually help. For example, if you feel anxious in crowds, you avoid them. Will this help you get over the fear?

The bottom line is that RFT proposes that rational thinking and problem-solving are not effective when it comes to overcoming mental health issues. Those can be dealt with differently. This is where ACT, an RFT-based therapy, comes in.

Why is acceptance so important?

Think of prehistoric times, when humans lived in caves. What helped those people survive, have children, and pass on genetic material to us in the 21st century?

They had to be constantly on the lookout for danger.

There might be a bear in that bush nearby. Those rustling leaves might mean an enemy clan is attacking.

Our minds still do that today. Did your boss make a weird face after talking to you? Did your partner put their phone away too quickly when you walked in?

Life experience was EVERYTHING.

When a caveman survived a bear attack, it made sense to replay it over and over in his head. He could learn a lot from the experience, even though it was traumatic.

We have a tendency to do the same with painful or embarrassing situations. We play it over and over in our heads, even though there is often little to learn from the experience.

Not fitting in was not an option.

Being liked and following the rules meant staying in the group and surviving.

In modern times, through the invention of TV and the internet, we are exposed to many more people. We have a lot more opportunity to compare ourselves to everyone and feel we are coming in short.

Those mechanisms are deeply ingrained into who we are. There is no way to control or get rid of these sensations, feelings, and thoughts. And most importantly, everyone experiences them.

An issue arises when we worry about experiencing them. They are not going to go away.

That is why acceptance is key. But where does this lead us? Are we automatically happy?

The happiness trap

Russ Harris, a world-renowned Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) specialist and trainer, puts forward a very interesting theory about happiness. It is made up of three parts:

- Being happy is not “a natural state”. Your mood is like the weather, everchanging.

- There is nothing you can do to always be happy. No one is.

- Happiness is not the goal. The goal is a rich and meaningful life.

Firstly, we all go through a range of emotions every day. Even the happiest day of your life will have elements of frustration, stress, sadness, and so on. Just like you can’t say sunny weather is the standard, neither is happiness.

Secondly, “normal” or “healthy” people, whatever you want to call them, are not constantly happy. Not struggling with a mental disorder or painful emotions does not mean a state of continual contentment.

And lastly, we shouldn’t strive to always be happy. We can do our best to live a rich and meaningful life, full of emotions. The danger of experiential avoidance is missing out on all of that.

When you take those three hypotheses into account, you are likely to experience more psychological satisfaction from everyday life.

Examine coping strategies that don’t work

The first step in ACT is to examine coping strategies in difficult situations you used in the past.

Did they work? If yes, how? If not, why?

ACT teaches you to distinguish between what you can and cannot control. Whatever you can’t change, you have to accept. Have a look at this FEAR vs. DARE model.

| vs. |

|

When you think of your painful thoughts and worries as part of yourself, it is very difficult to overcome them. Impossible, even, since you already accepted they are a part of you.

Instead, try to distance yourself from them, in order to come up with working solutions. ACT will help you learn how to do that.

Weighing each of your experiences and deciding whether they are positive or negative can also be very destructive.

Life is full of situations, both pleasant and unpleasant. You can’t get around experiencing the bad ones, too. Avoiding situations that give you feelings of anxiety or depression makes you miss out on a lot of what life has to offer.

And lastly, making excuses for avoiding experiences traps you in the situation you are in. And you already decided you want that to change, right? Let’s have a look at how we can go about doing that.

FEAR likely didn’t work for you in the past. Let’s DARE instead.

ACT principles and mindfulness skills

There are six core principles underlying techniques and strategies you can apply to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. You can think of it as a hexagonal diamond, where each of the tops is a piece of psychological flexibility.

The more you identify with those processes, the closer you are to the meaningful and fulfilling life. Try the ACT therapy techniques below.

An ACT therapist may decide the best path is to go one by one, to have them all come together at the end of your treatment.

Have a look at what the six core principles are all about. I have prepared some example exercises as well. Try to individualize them in order to have them help you best.

Acceptance (open up)

Life is not void of unpleasant thoughts and feelings. Accepting this premise is at the center of this approach. Worrying about things we have no control over just leads to further suffering.

Rather than trying to get rid of them, acknowledge the thoughts and sensations. Let them come and go without struggling.

When you begin to experience unpleasant thoughts or sensations, simply notice them. Allow them to be. Remember, to “accept” does not mean you like the feeling.

Cognitive defusion. (observe your thoughts)

Cognitive defusion allows you to look at thoughts “from the outside”. That way you can see them as what they are, just cognitions, not threatening or stressful parts of yourself. The goal is to explore them in different ways until they lose their emotional impact.

Picture a phrase you have been struggling with lately. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What is your mind telling you?

- Do you notice what your mind is doing?

Try to avoid phrasing these questions as starting with “Am I…” or “Do I…”.

Then inspect the answer. Can you see it or hear it? Can you imagine it written in a different font or pitch? Said by a funny cartoon character or written backwards? Or maybe as words on a karaoke screen?

At first, this may be difficult. With time, you may even laugh. Whatever you do, don’t try to silence or avoid the problem. That is what makes your mind “hook” onto the thought.

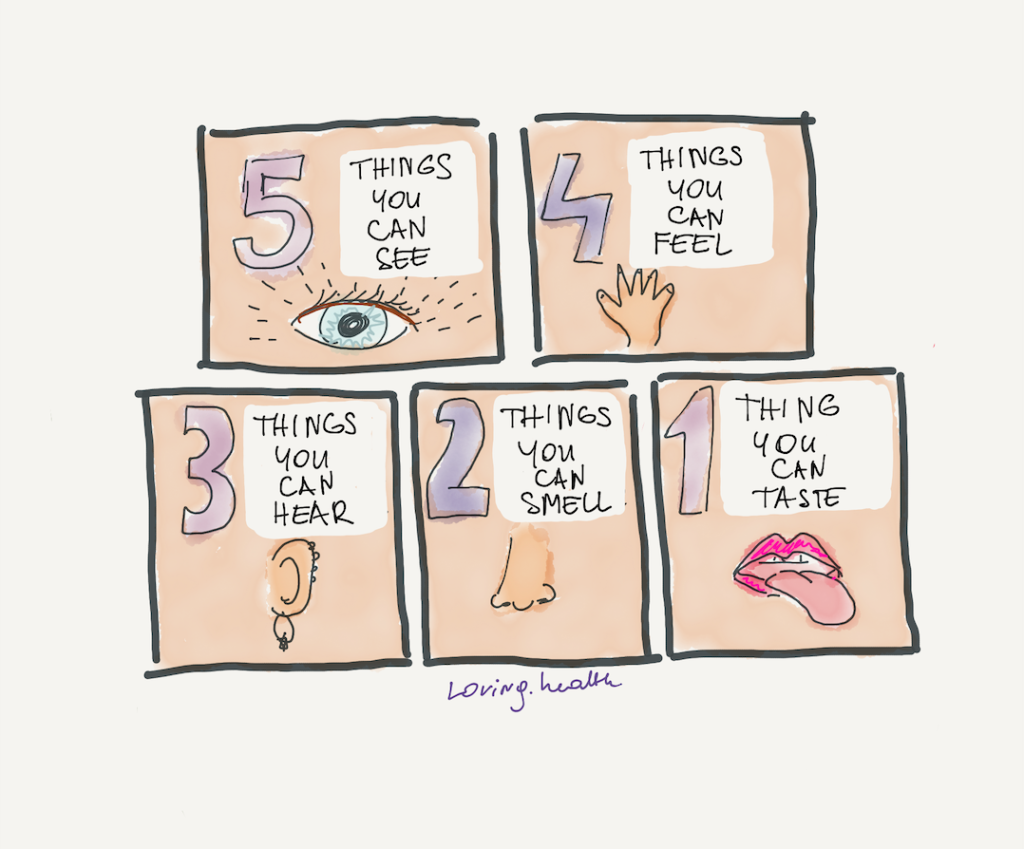

Contact with the present moment (be here and now)

You can’t change the past. You don’t know what the future holds. But the present moment is something you can experience. Being mindful helps you concentrate on what is important right now.

Developing a transcendent sense of self helps with grounding yourself in stressful situations. If any distracting thoughts pop into your head, let them come and go without struggling. When you begin fighting, you turn your attention away from what is happening right now.

The “basic recipe” for being present basically consists of three combinations.

1. Notice.

2. Let your thoughts drift away.

3. Let your feelings be.

You can create your own exercise or direct your attention to …

The Observing Self (a clean conscience)

The Observing Self is a process that lets you distance yourself from your private experiences, physical body and expectations from others. You are to look at those as an observer.

From this perspective, these phenomena are not threatening or dangerous as if you were watching a play. To put it another way: “You are heaven. Everything else is just weather” (Pema Chedryn).

The Observing Self can also be called pure awareness, that is, the awareness of one’s own awareness.

The observing self is a process closely related to mindfulness, and especially mindfulness directed at one’s own awareness.

This is an abridged version of the “Observer” exercise from a textbook by Steven C. Hayes and colleagues (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999).

1. Notice X.

2. There is an X - and there is You noticing the X.

3. If you can see X, you can’t be X.

4. X keeps changing, you who notice X remain unchanged.

While the situation changes, “you” remain yourself.

Values (knowing what’s important)

The last two of the six core principles are heavily intertwined. First, examine what your values are. Don’t look at what others are trying to achieve or be; concentrate on yourself and the life you want to live.

- Do you want to have more meaningful relationships?

- Or maybe you want to become more independent?

Everyone is different.

Once you decide what you want, you may be more willing to experience painful thoughts and feelings in order to achieve it. When the goal is something you don’t want anyway, you are unlikely to get out of your comfort zone.

The simplest exercise you can do to begin is to identify what your values are. It may be difficult at first and you might start to list out things that aren’t truly important to you.

Do this in private, don’t open yourself up to judgment. What is important to someone else may simply not be your priority and this makes the exercise moot.

It’s often difficult to come up with values on the spot. We have a great ACT worksheet to help you with this task.

Committed action (do what’s right)

The last of the six core principles is just as important as an engine in a car. This is where the word ACT comes in. Taking effective action towards values guided by the life you want to live is the cherry on top of everything you learned.

There are four steps to commited action:

1. Choose the area of your life that is important to you, in which you want to make changes.

2. Choose the values you want to follow in this area of life.

3. Set goals that will be based on these values.

4. Take action with mindfulness.

Are values and goals the same?

Goals are close-ended. When setting up a goal for yourself, all you are looking for is to “get there”. And what happens once you achieve it? Sure, you may feel a sense of success or even happiness. For a moment. How long until another goal comes along.

When you are goal-oriented, your entire life is just striving to reach some place or time. The journey and all life has to offer along the way are missed. What’s more, frustration is overwhelming if we fail to achieve something we set out to do.

Values, on the other hand, are open-ended. Have a look at these two examples:

- Goal: I want to graduate with a master’s degree.

- Value: I want to learn, gain skills, knowledge, and understanding of a topic I am passionate about.

Do you see the difference? With a value, there is no end-point. There is a lot less pressure and it is focused on something that can bring you satisfaction all throughout the journey.

If all your focus is set on that one day when you graduate, you not only miss out on enjoyment during your studies, but you are also left directionless at the end.

Sure, the next thing will be to get a great job. What if you don’t get it right away? How frustrated are you going to be having to wait to pick the fruits of your labor?

If, however, you enjoy the small things and satisfaction from your achievements along the way, it’s all going to be tripled once you reach graduation. The cherry on top of a cake.

What’s more, you may even feel the need to deepen your knowledge after your formal education is complete.

You never know where life takes you. You may be working towards one thing, but end up in a place you never expected. It doesn’t mean your efforts were wasted. If you enjoyed yourself along the way, well, then you avoided the happiness trap!

History of ACT

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy was created by Steven Hayes in 1986 and belongs to the so-called “third wave” of behavioral therapies. Third wave therapies also include:

- Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT),

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), and

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

They all focus on being psychologically present in the moment and developing mindfulness.

ACT has decades of research support. Over 300 randomized controlled trials have been conducted using the technique, showing positive results. How is this possible?

Well, before making it public, Hayes and his team spent many years investigating foundational principles, concepts, and techniques of existing therapies and extracting what works. Among other things, they looked at classical conditioning, negative reinforcement, and exposure therapy.

They started from the ground up. This allowed concepts and techniques they developed to be clinically effective and consistent with existing models.

Is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) a form of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)?

ACT and CBT are often confused. ACT has even been described as an “existential humanistic cognitive-behavioral therapy”.

While this is in many ways accurate, ACT does not concentrate on behavior change strategies to improve quality of life. The focus is on your thoughts and feelings, as well as being mindful in the present moment. In CBT, patients and therapists target actions that lead to mental issues at hand.

Perhaps there would be no ACT if it wasn’t for CBT, but they have different approaches to mental health and the way they treat Western psychology.

ACT final thoughts 🙂

ACT is a mindfulness-based therapy that may target anything from anxiety disorders to chronic pain. The goal is to accept all feelings, sensations, and thoughts, even ones that may not be pleasant. It makes the assumption that a meaningful life full of emotions is something attainable while avoiding sadness, pain, or restlessness is not possible.

When you are psychologically present in the moment, you are able to take action in a valued direction. A large amount of empirical research shows that this is effective.

ACT has been shown to help patients experience things they were previously not ready to commit to. If you feel experiential avoidance strategies are something you are guilty of, this may be a good suit for you.

Schedule your free online 30-minute consultation with an ACT therapist.

Hello! I’m a fellow ACT lover, blogger and a BCBA and I loved this post! So informative and helpful in spreading education on ACT. Eloquently written and educational!

Appreciate it, thank you!